10 yrs of ‘Make in India’ & the manufacturing sector is back to where it was in 2013-14

New Delhi: Even as the Narendra Modi government celebrates 10 years of the “Make in India” initiative, an analysis of the country’s manufacturing and export performance shows the push to the sector has not increased its share in the GDP, in employment, or in global exports.

The government launched the “Make in India” initiative on 25 September 2014 to facilitate investment, foster innovation, build best-in-class infrastructure, and make India a hub for manufacturing, design and innovation.

On the 10th anniversary of the programme Wednesday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi posted on X, saying “Make in India” illustrated the “collective resolve of 140 crore Indians to make our nation a powerhouse of manufacturing and innovation”.

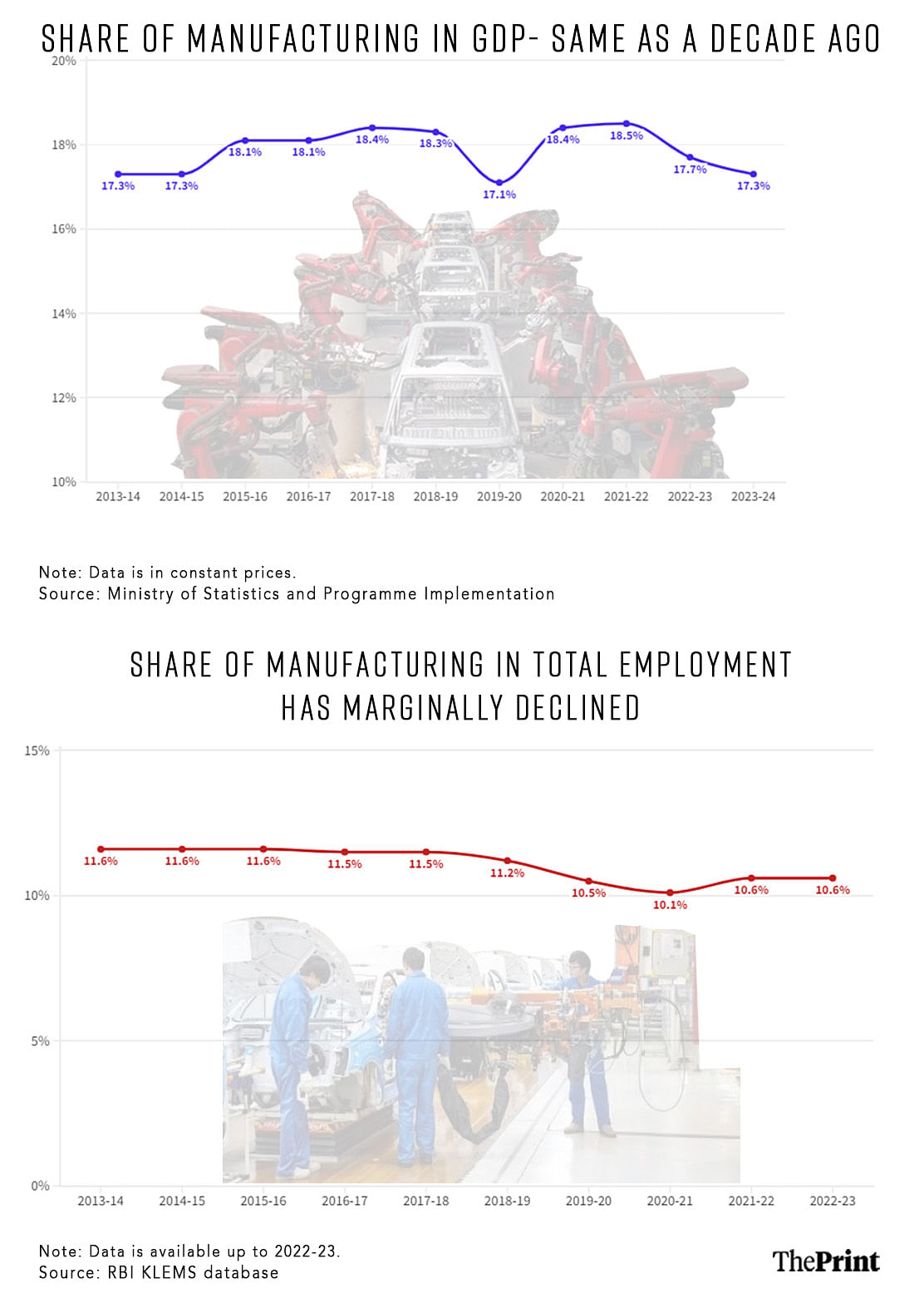

The government’s own data, however, shows the manufacturing sector has remained flat over the last decade in its contribution to the gross domestic product (GDP). Further, the sector’s share in total employment in the country has marginally declined over this period.

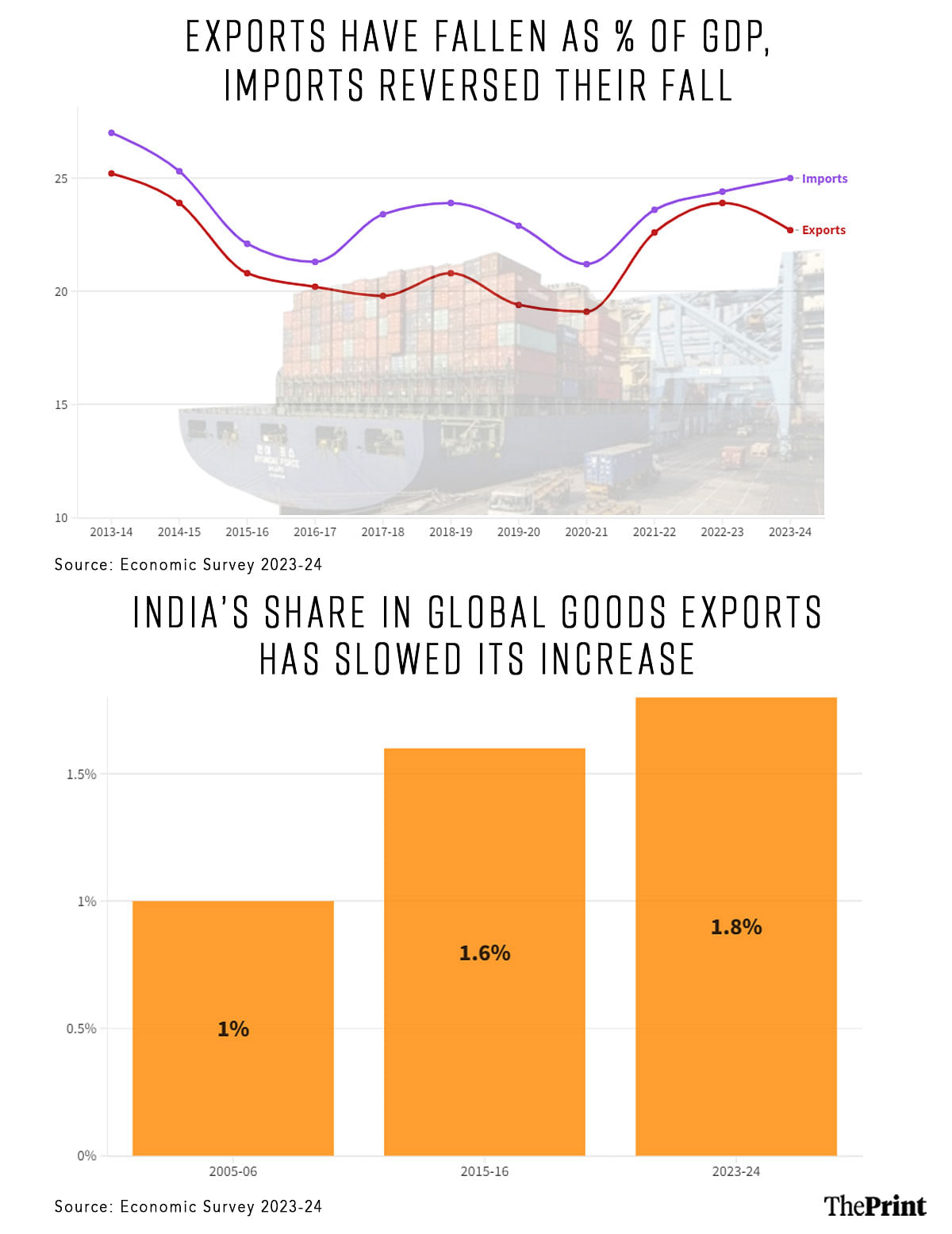

The country’s share in global merchandise exports has also largely stagnated over this period, and exports have seen a falling share in India’s GDP.

Manufacturing contribution unchanged

Data from the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation shows the manufacturing sector contributed 17.3 percent to India’s GDP in 2013-14, a year before the “Make in India” initiative was launched. This rose to a little more than 18 percent over the next few years, to peak at 18.5 percent in the post-pandemic year 2021-22.

Since then, the sector has seen two consecutive years of declining share in the GDP — 17.7 percent in 2022-23 and 17.3 percent in 2023-24, the same as it was in 2013-14.

In fact, data for the first quarter of 2023-24 shows the share of manufacturing has dropped further to 15.7 percent.

Additionally, the Reserve Bank of India’s KLEMS database shows the share of the manufacturing sector in total employment in the country has marginally declined from 11.6 percent in 2013-14 and 2014-15 to 10.6 percent in 2022-23, the latest period for which there is data.

In other words, while employment in the manufacturing sector has grown, the “Make in India” push has not resulted in manufacturing outpacing other sectors of the economy in employment generation.

Exports have not benefited

Another priority area for the “Make in India” initiative was to boost exports and cut down on imports. The data over the last 10 years revealed the programme has failed to do the former but has been marginally successful in achieving the latter, although even this improvement has recently been reversing.

That is, India’s exports as a share of GDP has fallen from 25.2 percent in 2013-14 to 22.7 percent in 2013-24. In Q1 of the current financial year, it stood at an even lower 21.8 percent.

Data from the Economic Survey showed India’s share in global exports has grown much slower over the last decade or so as compared to the 2005-15 period. In 2005-06, India contributed 1 percent to global exports. By 2015-16, this had grown to 1.6 percent. However, by 2022-23, it stood at just 1.8 percent — a significantly lower increase.

The World Bank, in the latest edition of its India Development Update released earlier this month, made particular mention of India’s poor export performance in terms of contributions to GDP, in global value chains, and in employment generation.

“India needs to diversify its exports and increase its participation in Global Value Chains (GVCs),” the report said. “Over the past decades, despite rapid overall economic growth, India’s trade in goods and services has decreased as a percentage of GDP and India’s participation in GVCs has fallen.”

“Exports are also relatively concentrated in goods and services that tend not to be labour-intensive,” it added. “As a result, trade-jobs linkages are not fully exploited.”

A major factor behind this decline, the report added, was the high import tariffs India imposes on key inputs used by India’s manufacturing sector. These tariffs, the report added, have raised production costs and made producers less competitive in international markets.

Perhaps due to these high tariffs, the data showed that “Make in India” has managed to marginally reduce India’s dependence on imports, although even this trend has reversed in the last few years.

While imports amounted to 27 percent of GDP in 2013-14, it fell to 21.2 percent by the pandemic year of 2020-21. Since then, however, this proportion has been rising, logging 25 percent in 2023-24 – just a little lower than where it was in 2013-14.

(Edited by Tikli Basu)

Also read: India mustn’t skip the manufacturing train. Services alone won’t tap into demographic dividend